Learn below about an international exchange on transformative memory between artists, activists and academics in Gulu, Uganda in May 2019, led by UBC Professor Erin Baines, School of Public Policy and Global Affairs, UBC Professor Pilar Riaño Alcalá, Gender, Race, Sexuality and Social Justice Institute, and Isaac Okwir Odiya of the Justice and Reconciliation Project.

Exchange participants with His Highness the Paramount Chief of Acholi, David Onen Acana II at Ker Kwaro Acholi: the cultural chiefs provided an overview of how they understood memory as transformative in relation to the violence endured since slavery and colonization. Photo by Michael Ruffolo.

In Acholi, northern Uganda, mango trees are like relatives. Their branches stretch out and provide shade for completing the rhythms of daily work, for self-reflection and to share teachings of the land. UBC PhD Candidate Ketty Anyeko reminds us that in Acholi, “mango trees are stories themselves and stories are told under them.” Mango trees witness the ebbs and flow of life and death, changes in relations and in relation to land, animals, rivers and the places. In the folds of colonialism, slavery, state repression and a near 30-year war in northern Uganda, mango trees remember. They hold space for collective memory, such as the torture endured Bucoro, where annual prayers take place. They are markers of personal memory, such as Consey, a woman from Atiak who recalls the war each time she passes a certain tree. They are sites for memory transmission, the community in Lukodi gathers under the mango tree to reflect on the massacre that took place there. Mango trees are planted on graves for memory, people are named after forests. The trees drop their mangos selectively, as if to nudge the recipient to not only remember but to take action.

Landscapes that remember: Consey, a community based memory worker, brings participants of the exchange to sites of memory in Atiak, Uganda. It was under this tree she was abducted by Ugandan rebels. Photo by Erin Baines.

Between May 20-24, 2019, 30 artists, activists, cultural leaders, survivors, and scholars participated in an international exchange to consider Acholi ways of knowing, remembering, relating and being. Hosted by the Justice and Reconciliation Project (JRP) in Gulu, Uganda, exchange participants engaged in community-led dialogues, visited houses and sites of memory, and considered how memory is transmitted through music, poetry, theatre, the body, sound, ritual and in the land, mountains, water and mango trees.

International participants from Indonesia, Colombia and Canada joined Ugandan participants from the Families of the Disappeared, Music for Peace, the Women’s Advocacy Network, Ker Kwaro Acholi and survivor associations and memory workers from Pabbo, Atiak, Lukodi and Bucoro. Although the histories and experiences of violence were different, connections were made between the work of memory and the repair of relationships that transcended time and space.

Royal dancers perform at Ker Kwaro Acholi, the Royal Palace; Exchange participant and Music for Peace artist, Jeff Korondo performs in a closing event for the public on JRP grounds. Photos by Michael Ruffolo.

Poet and UBC PhD Candidate Juliane Okot Bitek reflects on memory practices that transcend: “I was part of the group that visited Burcoro, where community that shared stories of two massacres that took place on their land. During the visit, Peter Morin offered to sing two songs. As he did not have his drums with him, he asked that we clap along with him and he provided the rhythm for us to follow. After he sang, a man stood up, evidently moved by Peter’s song, and asked if people remembered that Acholi used to have a similar kind of song. He then sang a song from memory, clapping along, as Peter had just done.”

The international exchange was the first of two over a three-year project by the Transformative Memory International Network, led by co-principal investigators Pilar Riaño Alcalá and Erin Baines. The two UBC professors seek to foster innovative and creative ways to think about and with memory after mass violence. “Knowledge generation in the partnership is centred on exchanges in order to move away from the ‘expert’ to foster co-learning, creation and listening”, said Professors Riaño and Baines at the first gathering of the exchange.

Gender researcher Docus Atenyo of JRP reflected on the methodology, “The dialogues in the communities were so interactive; for example, it gave a platform for experiential sharing and learning for both the visitors and the local community. These exchanges removed any misconceptions that Acholi community members had e.g having a feeling that only black people suffered different violations. All countries that have gone through conflict of any nature have similar experiences and violations although the context and perpetrators might be different.”

Through exchange, participants explored critical questions such as what makes memory transformative of relationships, whether to each other, the dead, or the land; how does memory transform social contracts and state policies; and, how do place based and relational ways of knowing inform ways of being, and being together? For Docus Atyeno “Memory is transformative when it promotes truth telling (acknowledgement of the wrong) and accountability among people; leads to restoration of harmonies and transcends political discourse. Past memories does not determine your future but it takes an action to make a better future.”

For a youth leader in Atiak, the future is how one cares for the environment. Speaking in a community dialogue and referencing the rapid deforestation in the area, he advised that “reconciliation cannot be done when life is not there, if we sit with where there are no trees or grass, can we breath? We survive because of the environment…if we are letting the memory grow, let it grow from all things”.

After stating that, “conflict took long and transformation is taking place very slowly,” a young man in Lukodi asked international visitors if it was the same in their country. Others wanted to know how they remember and if they also erect monuments. The next day, during the morning session one participant reflected how the exchange moved participants to make connections, to trace and encounter the resonances.

Each exchange participant was tasked with being their own ‘documentarian’ during the exchange, either through written reflections, photographs, voice recordings, video or art. Such documents will become part of a Digital Archive hosted by the Partnership, which can be drawn upon when co-applicants want to explore the topic in their respective work and work with others, and where connections continue to be made across experience and theories of transformative memory have begun to emerge.

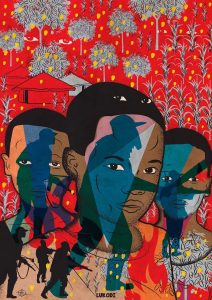

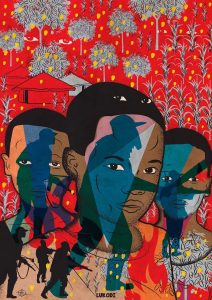

Indonesian artist Alit Ambara sketched the exchange throughout the five days, conceptualizing and representing memory visually. Drawing on knowledge transmission of a community performed theatre of the Lukodi massacre, he refined his work in a series of posters.

Exchange participant Irene Oyik, Atiak Truth and Reconciliation Committee and a trained counselor and theatre facilitator, holds one of the toy guns used in community theatres to recreate historical events and to teach the next generation about the war. Photo by Michael Ruffolo.

Professor Maria Emma Wills of the National University of Colombia reflects on what memory means to her based on her work in Colombia but in relation to the exchange in Uganda, “For me, memory is a creative process by which stories/symbols take shape and weave a thread between representations of who we have been and where we come from; who we are at present and where we stand; who we might become in the future and what we might struggle for. On the other hand, memory is relational and situated in the sense that it comes from a permanent and dynamic communicative practice between our own voice and body, and that of others – friends, foes, relatives, ancestors, peers, authority figures, and nature and landscapes as I learned from ethnic communities in Colombia and survivors in Gulu.

In Gulu, most Exchange participants came from countries, communities and/or nations/people that have survived excruciating experiences, be it wars or ethnic or political genocides. In all of them, change is expected to occur, allowing ‘you to think and act, and be a better person’ and live in a better way, at a personal, a community, a people, or a national level.”

For Ambrose Olaa, Prime Minister of the cultural institution Ker Kwaro Acholi, transformative memory transcends legal systems or transitional in government. It involves recognizing what happened and accepting it – personally and societally – so that a process of recovery and action begins over a long process and across generations. “This is not a circular process of recovery, but to reach a new state of being” in which one is responsible for another, and the dead are summoned and sent to the world of ancestors. Reflecting on the exchange, a Ugandan student offered that, “I am here to learn from all of you, but maturity does not come with age but acceptance of responsibility.”

The next international exchange will take place in Colombia in 2020, developing the conceptual themes emergent including, intergenerational memory between the living and between the living and the dead; transformative memory as connectivity; memory of the missing and disappeared (memory where there is no one to remember) and social movements of memory and politics of memory.

The Transformative Memory International Network is housed at the University of British Columbia in partnership with JRP, the National University of Colombia, the University of Guelph and the Indonesia Institute of Social History, explores ways memory is employed to address the responsibility persons have towards the well-being and rights of others in the aftermaths of mass violence.

The network seeks to strengthen relations between partners and place-based and relational memory praxis. It is funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Partnership Development Grant (Pilar Riaño-Alcalá and Erin Baines), the Ivan Head South-North Chair, the Hampton Fund, the Dean of Arts research fund and with the support of the Social Justice Institute and the School of Public Policy and Global Affairs at the University of British Columbia.

Exchange participants visit the memorial in Burcoro, a village in Awach sub-county, for victims and survivors of an NRA operation where civilians, accused of being rebel supporters, were tortured, sexually violated, abducted and killed over the course of four days in April 1991. Photo by Erika Diettes. |   Indonesian Artist Alit Ambara visually documented the exchange: illustrated here a theatrical performance in Lukodi. |

|---|---|

Royal dancers perform at Ker Kwaro Acholi, the Royal Palace; Exchange participant and Music for Peace artist, Jeff Korondo performs in a closing event for the public on JRP grounds. Photos by Michael Ruffolo. |   JRP Gender expert Dorcus Atyeno explains the importance of storytelling and family reunification after the war in Acholi during the exchange. Photo by Michael Ruffolo. |